In the middle of the 4th Century AD, Saint Frumentius brought Christianity to the Axumite Kingdom in what is now northern Ethiopia. According to local tradition the churches in the Gheralta Mountains were constructed in the 4th Century by the first Christian kings of Ethiopia, Abraha and Atsbeha.

Many of the hermitage caves were expanded to become the enormous edifices that can now be admired flickering in candlelight amid the murmurs of the cream-shawled faithful. The churches have been hewn directly out of the mountainsides by hand, only their slim rock pillars left in place to prevent collapse.

The churches are found in high, remote places to fend off would-be attackers and I have occasionally heard Ethiopia referred to as ‘The Tibet of Africa’, which I do not think an outlandish statement. Intrepid Irish explorer and travel writer Dervla Murphy notes in the prologue of her wonderful account of In Ethiopia with a Mule, first published in 1968, that:

“There is a certain similarity between the developments of Ethiopian Christianity and Tibetan Buddhism. In both cases, when alien religions were brought to isolated countries the new teachings soon became diluted with ancient animist superstitions; and so these cuttings from two great world religions grew on their high plateaux into exotic plants, hardly recognizable as offshoots of their parent faiths.”

[Image from Abuna Yemata church - see below]

A church service at Yohannis Maqudi

We ascended up to our first rock church through the gateway of the priests’ dwelling, a large dry stone construction of sandy red rock; the rectangular stones placed together as well as you could hope to see anywhere. The Tigrayans, in their arid, rocky plateaux, mainly live in dry stone buildings compared with much of the rest of the country whom, in their lusher pasturelands, use wood and dung to construct their homes.

I stepped through the roofed archway of the outer wall, a large iron bell hanging from a sturdy beam. Three snotty nosed ten year-olds were loitering in the entranceway and flashed insecure smiles at me. Some women were sitting in the shade of an acacia tree. I dropped my pack and carried on through a gap in a stone wall along a thin path leading around to a cliffside. As I rounded the corner I came across six women and an elderly priest standing at the entrance to a doorway cut into the cliff, framed with wooden beams and a thick door hanging open with the sound of chanting and prayers emanating from the gloomy inside.

This was the rock-hewn church of Yohannis Maqudi. The women all wore cream shammas and had beautifully braided hair; thin and tightly woven in different angular patterns down on the front section of their heads, their long wavy afro curls then either flying out at the back in large waves or in continuing carefully arranged linear folds and designs. Often they wear a single large silver-coloured earring high up on their left ear that hangs in an upturned crescent.

Frescos in the church then outside to drink talla

The frescos, painted onto the hand-chiseled walls, were from another time, another world: men with swords were arranged in a row of horses ready for battle. Two demons had got hold of a man and while one held him upside down by his feet the other poked him in the eye with a spear. Warrior saints, the twelve apostles, and Fasilides, Emperor of Ethiopia 1632 – 1667, were all speaking to me through speech bubbles written in Ge’ez, the ancient language of the Ethiopian Christian Church. Their eyes all flashed menacingly.

The priests continued to chant with the congregation occasionally murmuring replies in response. After the mass the women all filed out through the door I had entered by and sat outside under the shade of the acacia. The men all left by the other door and walked to the priest’s quarters where they and I sat on earthen benches around a sunken floor. We drank talla, the millet-based beer, and ate the spongy injera with a chili sauce as everyone was fasting for Genna, the Ethiopian Christmas taking place in a week or so.

We came down through a lush eucalyptus grove, over a dry sandy riverbed then up the other side on a path cleft through steep earthy orange embankments. A small freestanding church was nestled into the side of the cliff up on our right hand side. Its tin roof and cross on top painted in pleasing bright colours. A bird darted across the valley with oily black feathers and bright auburn wing tips. As we came to the top of a small hill, the dry stone wall-lined fields of an idyllic valley opened out before us. Young girls playing next to a huge pile of teff were screaming their heads off as I slowly walked down the track “faranji! [foreigner!] hello! farangi! hello! farangi…” as a never-ending welcome.

The valley was a patchwork of perfectly leveled fields dotted with acacia, olive and eucalyptus. Cacti ran in thick groves, used as a natural fencing around the properties. A peach sunset warmed the sky in the west with rays of gold slanting down beneath fluffy cumulonimbus in shafts onto the valley floor. To the east, Mariam Bagulisha, a gently domed pinnacle of rock, sored up from the flat ground into a dreamy sky, cartoon-like in the half-light. I felt too ethereal to be real.

Abuna Abraham church

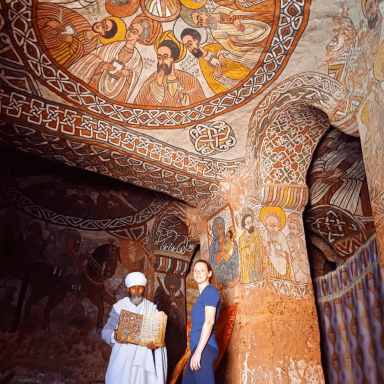

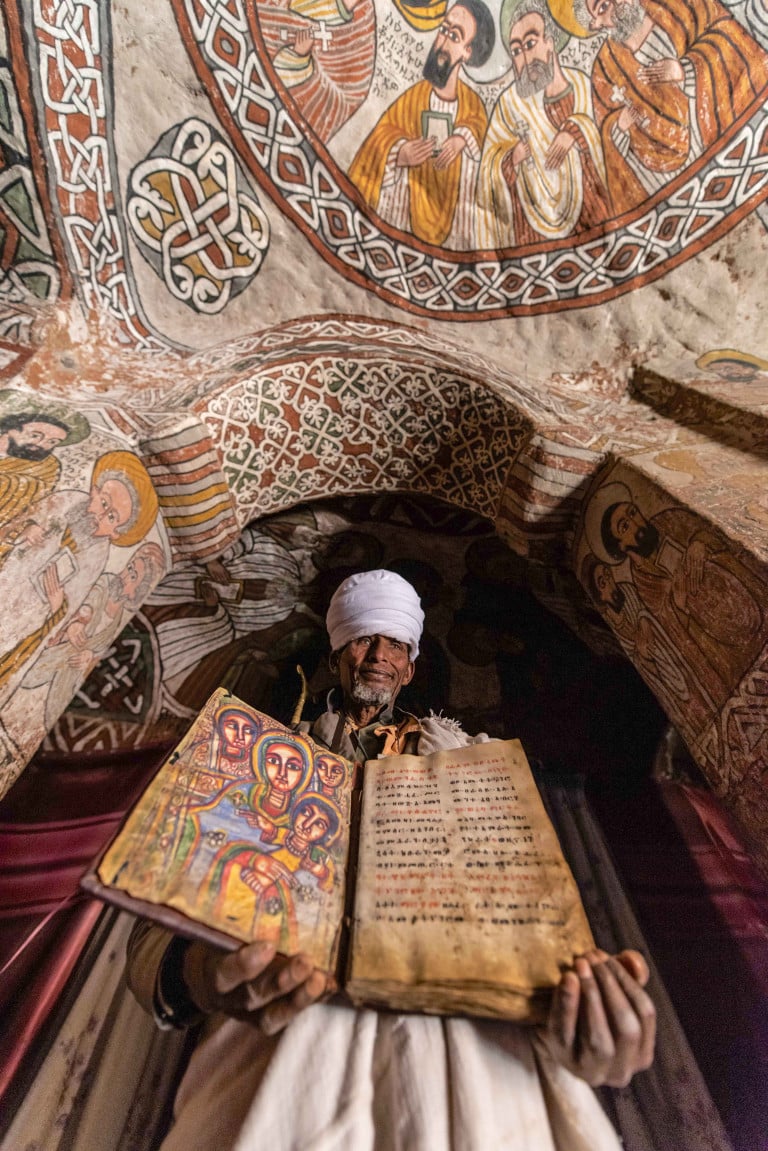

In the morning we set off through the valley to tackle the steep ascent to the church of Abuna Abraham, the largest in the Gheralta Mountains. Located at the top of a sheer cliff, the church overlooks a long stretch of plain far below. Its interior is nothing short of magnificent; eleven huge pillars of living rock souring up to the vaulted ceiling covered in colourful 7th Century frescos showing the deeds of Abuna Abraham himself. Bennie gave me a rundown of the images: “Once upon a time there was no water and the people were thirsty so the saint placed pots of water on a lion’s back to bring to the Christians,” as he pointed to the painting of the beast above the doorway.

“And here, once when he was walking from Amhara to Tigray, a large lake prevented him and his followers from completing the journey, so he placed the cross at the end of his staff into the water like Moses and the waters parted and they were able to cross.” In the fresco depiction his eyes are shining white with a holy light as his staff touches a rectangular box of water with fish painted at odd angles over the stone. Another depiction shows the saint holding a large young male lion so its smaller brother can suckle his mother.

An English lesson

We lounged under the largest sycamore tree, its incredible branches reaching out over fifteen meters from its huge twisting trunk. Birds of all kinds, colours and calls, had flocked to this marvel and it was a delicious feeling to lie in the long grass eating peanut butter sandwiches and listen to their chatter. This would have been an ideal campsite but it was still only mid-afternoon and Bennie and I fancied some company again so we eventually loaded our packs and continued on. That night I stayed at the house of Haile, a member of the guiding association in the Gheralta. He was not home when we arrived but his wife, Gabriel, took great care of me alongside her seven children, even though my arrival had not been pre-arranged.

An impromptu English lesson began with her daughter Terhaus, an incredibly bright ten-year-old girl in the 4th grade, and her son Hamben, a twelve-year-old in the grade above. They would scribble down words in English that I gave them: ‘House’. ‘Cow’. ‘Mother’. ‘Light’. I corrected the spelling and then they would write the words again on the back of the paper to prove they weren’t cheating, although they often did, inviting squeals of remorse when I tickled them as punishment.

The following day I reached the entranceway to the freestanding church, a sandy path leading up from a stone-roofed gate to where about forty men and women were milling about or sitting in the shade of the eaves of the roof. It had hundreds of tin tassels suspended from the eaves, making a pleasant tinkling sound in the breeze. The men of the group turned out to be a work party and showed me the inside, which was filled with mounds of shoulder-high sand.

I was surprised and excited to find that the freestanding church actually led back into a massive rock-hewn hall cut into the mountainside, its many pillars curving up and out at the top into an exquisitely carved chequered stone-cut pattern on the ceiling. Their frescos of the pillars had fallen away to time and disrepair and there was much erosion of the stone. It was here that the men were working. It was a very authentic experience to be in one of these marvels with many bodies milling about around me, the chink chink of chisels striking the stone floor.

Abuna Yemata Church (the most famous one)

During the late 5th Century, nine saints travelled as missionaries to Axum and were influential in the growth of Christianity in the region. Although legend has them all as Syrian in origin, many have been traced back to Constantinople, Anatolia and even Rome. Welcomed by King Ella Amida in Axum in the north, the son of the first Christian kings, the nine ‘Syrian’ saints then made their separate ways into the country, founding different churches and monasteries as they went. One of the nine, Saint Yemata Atan, came to Gheralta and legend has it that he rode his horse up the sheer wall to carve the church now named after him; his horse’s hoofmarks still imprinted and visible in the stone....

Visiting the famous Abuna Yemata Church I practically skipped up the short ascent to the base of pillars. The ascent then became very steep to the point where I was climbing with ropes and a provided harness over a particularly tricky section. There are always several local men who are used to helping up tourists at this tricky section. Upon reaching the top of a massive boulder, wedged about halfway up between the two largest stone towers, I met a small group of Spanish tourists. I chatted with their tour leader for a while, both of us equally rejoicing in the beauty of the mountains and bemoaning our fear of vertical heights.

From the top of the wedged boulder we could see that windows of Abuna Yemata Atan Guh (“Akuna Matata?”) had been cut into the side of the largest pillar. To get inside we had to shuffle along a meter-wide ledge with a sheer unprotected vertical drop on the left that goes down may hundreds of meters, although I’m not exactly sure of how many as I didn’t look. Then you duck inside a small round hole and again you are awarded with the cool, damp, mind-blowing interior of a place that shouldn’t exist. It is a truly incredible experience.

Mariyam Koko church

For those unable or unwilling to make the climb there is the equally impressive option to visit the church of Abuna Mariyam Koko, which is a short drive from Abuna Yemata. The climb is more regular although I chose to do this particular ascent in the dark at four o’clock in the morning. The reason being that it was Genna [Ethiopian Christmas], and I wanted to see the holy mass that is performed throughout the night for the occasion. After making the ascent to the church by torchlight, we were greeted by ten priests who were standing in the middle of the beautifully carved church.

One of them was beating a huge leather drum covered with cowhide, held in place by a thick leather strap over his shoulder. He had a pointy beard like a Spanish Conquistador and did a little dance as he beat both ends loudly and rhythmically. The other priests stood around him in a circle singing and shaking their metal rattles in time. Waves of incense filed the air. The music was hypnotic and through a microphone was played out from a round speaker wedged in a small hermitage window cut into the side of the mountain, the wailing prayers drifting down the 400m cliff face to the houses and farmsteads below.

I went outside at first light to watch the sunrise over the mountain chain next to the tannoy speaker, a priest in turn wailing like a Muezzin then praying very low and fast. The ledge I was standing on fell away in a perfectly vertical drop to the flat Tigrinyan farmsteads on the tableland below, on my right the Gheralta chain rising to attention like soldiers on morning parade. Before the sun rose over the horizon it ignited a small line of fluffy clouds directly in front of me in a searing coral through to gold, so bright I couldn’t believe my eyes could take in a colour like that without burning. It was very cold. I waited for the sun to come up with my teeth chattering and the wail from the tannoy reverberating in my ears.

This blog is taken from part of a chapter of:

Wax & Gold: Journeys in Ethiopia & other roads less travelled

By Sam McManus